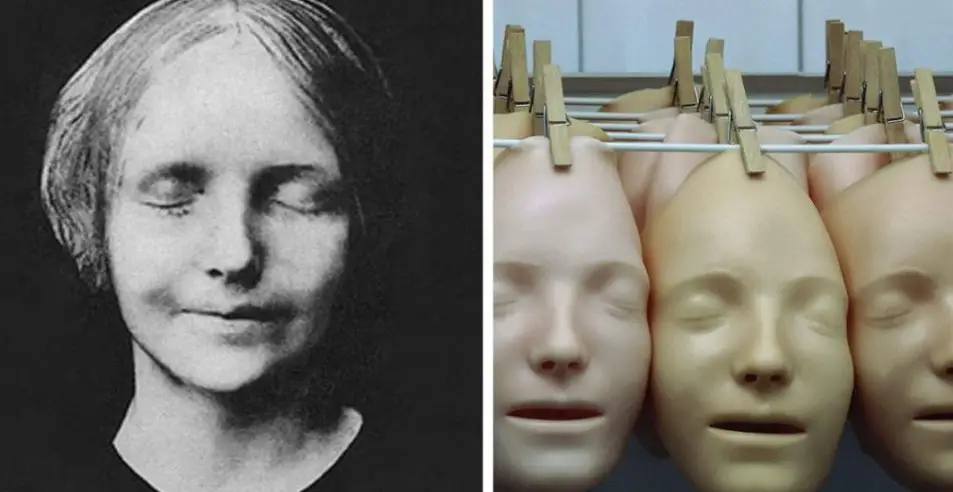

How a Girl’s 1800s Death Mask Became the Face of CPR Dolls

You’ve probably seen her face in a first-aid class—lifeless, serene, and eternally waiting for a lifesaving kiss.

Meet Resusci Annie, the CPR dummy used by millions to practice chest compressions and rescue breaths.

But here’s the twist: her face isn’t fictional.

It belongs to a nameless teenage girl pulled from Paris’s Seine River in the 1880s, whose hauntingly calm expression became a global icon of survival. Talk about a glow-up from tragedy.

From Riverbank to Bohemian Chic

The girl, believed to be around 16, was found drowned with no signs of violence.

Suicide was the leading theory, but her identity remains a mystery. Parisian mortuary workers, struck by her “serene” half-smile, commissioned a plaster death mask—a common practice for unidentified bodies back then.

But this wasn’t just another morbid souvenir. Copies of the mask, dubbed L’Inconnue de la Seine (The Unknown Woman of the Seine), flew off Left Bank workshops.

Soon, her face adorned artists’ studios and literary salons.

Albert Camus called her the “drowned Mona Lisa,” and her enigmatic grin sparked wild rumors: Was she a jilted lover? A runaway aristocrat? A twin from Liverpool?.

By the 1920s, her mask was a macabre must-have for Parisian hipsters.

“People hung her face on their walls like a gothic decor trend,” says Dr. Stephanie Loke, co-author of a recent BMJ paper tracing Annie’s origins.

“Imagine having a dead stranger’s face in your living room today. Creepy, right?”.

CPR’s Brutal Beginnings

Fast-forward to the 1950s. CPR was revolutionary—but practicing it? A literal pain.

Trainees bruised each other’s ribs and risked spleen injuries. Enter Dr. Archer Gordon of the American Heart Association, who dreamed of a dummy to spare students the agony.

He teamed up with Norwegian toymaker Åsmund Laerdal, whose soft plastic dolls were already a hit.

But Laerdal had a personal stake: he’d once saved his son from drowning.

The challenge? Designing a face trainees wouldn’t mind kissing.

Laerdal remembered a mask hanging in his grandparents’ home—L’Inconnue de la Seine. “Her peaceful look made her the perfect candidate,” says Dr. Sarah McKernon, Loke’s co-author.

In 1960, Resusci Annie was born, her collapsible chest and parted lips revolutionizing CPR training.

Annie Goes Global—With a Side of Michael Jackson

Laerdal’s company pivoted from toy cars to medical devices, and Annie became a superstar.

Over 300 million people have trained on her, saving an estimated 2.5 million lives.

Even Michael Jackson immortalized her in Smooth Criminal: “Annie, are you OK?”—a direct nod to the dummy’s training script.

But let’s be real: Annie’s design wasn’t flawless. Early versions lacked realistic features like breasts, skewing practice toward male anatomy.

“It’s harder to position hands on a curvier chest,” admits one paramedic in online forums.

Modern manikins now include diverse body types, but Annie’s face remains unchanged—a eerie bridge between past and present.

Ethics of a Posthumous Supermodel

Here’s the elephant in the room: using a dead teen’s face without consent.

In the 1800s, death masks were routine, but today? “Deeply unethical,” argues ethicist Julian Sheather in a BMJ editorial.

“Imagine your loved one’s face sold as a doll.” Yet Sheather treads carefully: “We can’t erase history, but today, we’d anonymize her”.

The debate isn’t just academic. Lorenzi, the Parisian studio that crafted the original mask, still sells replicas labeled Noyée de la Seine (Drowned Woman of the Seine).

For €200, you too can own a piece of CPR history—or, depending on your view, a commodified tragedy.

A Legacy of Life and Lingering Questions

Annie’s story is a paradox: a girl lost to the Seine became a symbol of survival, her face kissed by strangers in the name of science.

Yet her anonymity strips her of agency. “She’s saved millions, but we’ll never know her name,” Loke reflects. “It’s beautiful and unsettling.”

For now, Annie’s plastic lips keep teaching the world how to breathe life back into others.

And somewhere in Paris, her death mask still stares from studio walls—a reminder that history’s ghosts often linger in the unlikeliest places.