Discover Mackinac Island: Michigan’s Car-Free Haven with 600 Horses, Historic Forts, and Over 1 Million Annual Visitors

- Mackinac Island, nestled in Lake Huron, has banned motorized vehicles since 1898, creating a serene, horse-powered paradise.

- With a population of around 583 residents and nearly 600 horses, the island maintains a unique ratio that supports daily life and tourism.

- As part of Michigan’s Great Lakes region, it draws over 1.2 million visitors yearly to its state park, fudge shops, and timeless attractions.

In the heart of Michigan, often dubbed the car capital of the world due to Detroit’s automotive legacy with giants like Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler, lies a striking contrast: a small island where vehicles are absent, and horses rule the roads.

Mackinac Island, a 4.35-square-mile gem in Lake Huron, offers a glimpse into a slower, more intentional way of life that has endured for over a century.

This vehicle-free enclave, accessible only by ferry from Mackinaw City or St. Ignace, invites travelers to step back in time amid crystal-clear waters and lush forests, but what secrets does its no-car policy hold, and how does it shape daily existence?

The ban on motorized vehicles dates to 1898, when a car’s backfire startled local horses, prompting village authorities to prohibit internal combustion engines.

By 1900, this rule extended across the entire island, a decision that has preserved its tranquil atmosphere ever since.

Today, even golf carts are forbidden on the streets, leaving the sounds of honking to the island’s geese or owls rather than traffic.

Residents and visitors alike navigate the 3.8-square-kilometer landscape by foot, bicycle, or horse-drawn carriage, fostering a pace that stands in defiance of modern haste.

Indigenous communities, particularly the Anishinaabe people, have ties to the island stretching back thousands of years.

They named it Michilimackinac, meaning “place of the great turtle” in Anishinaabemowin, inspired by its limestone bluffs and forested ridges resembling a turtle emerging from the water.

Archaeological evidence reveals burial sites dating back roughly 3,000 years, underscoring its sacred status in Great Lakes history.

French Jesuit missionaries and fur traders arrived in the 1650s, establishing it as a key trading hub.

British forces built a fort in 1780 for defense at the confluence of Lake Huron and Lake Michigan, a strategic spot that saw action during the War of 1812 before passing to American control.

By the late 19th century, the island transformed into a summer retreat for wealthy industrialists from Chicago and Detroit, drawn to its pristine shores and fresh air.

This era birthed iconic structures like the Grand Hotel, opened in 1887, which boasts the world’s longest porch at 660 feet and rooms individually decorated in Victorian style.

The hotel’s appeal remains strong; Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer recently suggested it as a filming location for HBO’s The White Lotus, highlighting its enduring glamour amid the island’s car-free charm.

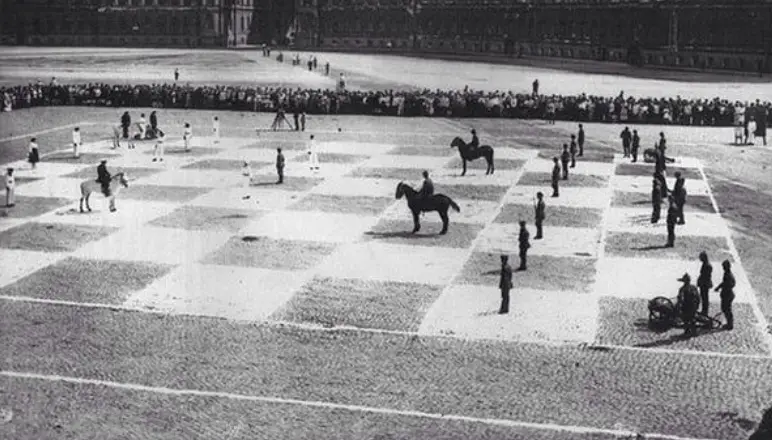

Life on Mackinac revolves around its equine inhabitants. Approximately 600 horses arrive each spring from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula to handle everything from garbage collection to FedEx deliveries and taxi services.

In winter, only 20 to 30 horses stay to maintain essential operations, as ice floes sometimes isolate the island from the mainland.

This reliance on horses not only sustains the no-car tradition but also infuses daily routines with a rhythmic clip-clop that transports visitors to a bygone era.

One local business owner, who has lived there since the 1990s, describes the experience of biking through tree-lined paths as a daily ritual that sets a peaceful tone, where greetings among neighbors are commonplace.

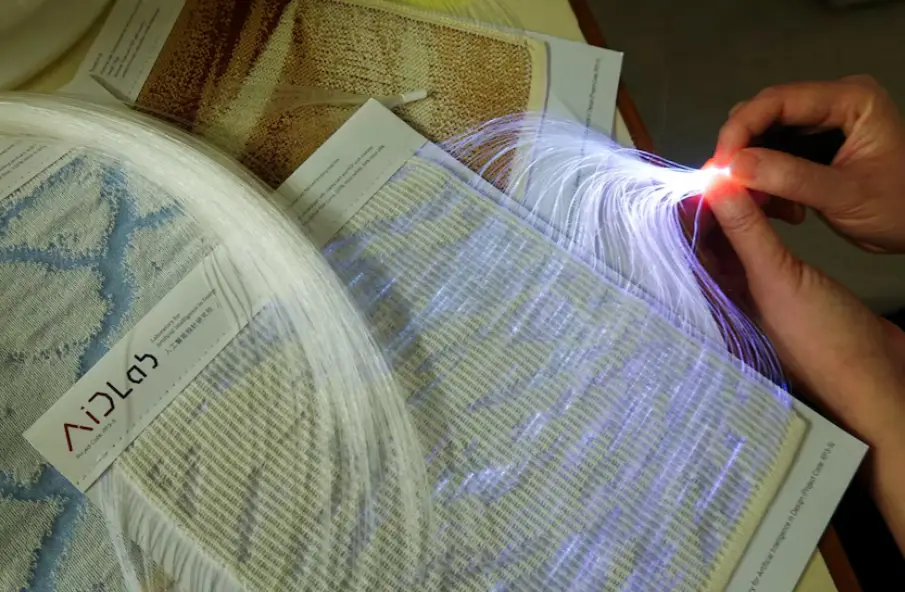

The island’s economy thrives on tourism, with fudge production as a signature industry. Shops along Main Street craft the treat on marble slabs, a method that draws crowds eager for samples.

Biking reigns supreme, with 1,500 rental bikes available, earning Mackinac the title of bicycle capital of the world.

The 8.2-mile M-185, the only U.S. highway without cars, encircles the island, offering stunning views of the five-mile Mackinac Bridge and access to pebble beaches and woodlands.

Eighty-two percent of the land falls under Mackinac Island State Park, where hikers and riders explore 70 miles of trails, towering limestone formations like the 50-foot Arch Rock, and old-growth forests.

Yet, what hidden layers lie beneath this picturesque surface, from revived Indigenous narratives to emerging modern twists?

Lodging sees upgrades too, with the Inn at Stonecliffe reopening after a $40 million restoration, featuring luxury cottages, a revived apple orchard, and Horsey’s Pub.

The Grand Hotel restores its original roofline and adds a Behind the Scenes Kitchen Tour, where guests peek into 136-year-old operations.

New dining spots like Mackinac Island Cookie Co. offer giant fresh-baked treats, while Mission Point Resort’s Lilac Lounge serves craft cocktails with lakeside views.

Transportation improvements bolster accessibility: revived ferry services increase frequency by 10 percent, with later departures for evening explorers.

United Airlines adds direct flights from Chicago to nearby airports, and new mobility scooters aid those navigating hilly terrain.

These updates ensure Mackinac remains inviting, yet one wonders how this delicate balance between preservation and progress will unfold in the face of growing crowds.

Amid whispers of overtourism, locals guard their haven’s secrets, like quiet north-end trails or winter isolation when snowmobiles briefly appear.

As you pedal along M-185 or sip fudge overlooking the marina, the island’s allure builds, leaving you to ponder: what undiscovered path might lead to its next revelation?