Meet the Man Who Climbed 700 Skyscrapers Without Equipment

Picture this: It’s 1916, and a crowd of 30,000 people in Omaha, Nebraska, crane their necks upward, clutching their bowler hats as the wind whips through the streets.

High above them, a man in a crisp suit and round glasses clings to the Omaha World-Herald building like a spider.

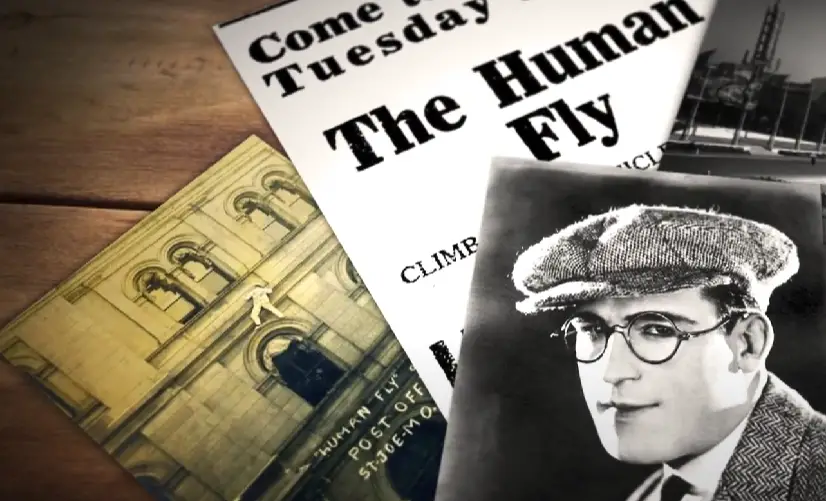

No ropes. No harness. Just his bare hands and a grin that says, “Watch this.” That man was Harry Gardiner—better known as “the Human Fly”—and his gravity-defying stunts made him one of the most jaw-dropping celebrities of the early 20th century.

Let’s be real: If someone tried this today, they’d be swarmed by police drones before reaching the third floor.

But back then, Gardiner turned skyscraper climbing into a lucrative art form, scaling over 700 buildings across Europe and North America in ordinary street clothes.

Ordinary street clothes! Imagine your grandpa’s wool suit being the only thing between him and a 50-story drop.

The Rise of a Daredevil

Gardiner’s era was a time of rapid change—skyscrapers sprouted like steel weeds, Charlie Chaplin’s silent films captivated audiences, and men traded silk top hats for derbies.

But while most folks were busy with the latest fads, Gardiner was redefining what it meant to be a showman.

His breakout moment came in 1905 with a climb up New York’s 150-foot Grant’s Tomb, a feat that landed him newspaper headlines and the nickname “the Human Fly”.

How did he do it? “Exceptionally strong hands,” historians say, though he occasionally used a short rope.

But let’s not undersell his charisma. Gardiner wasn’t just climbing—he was performing.

With a camera-ready smile and a flair for drama, he turned each ascent into a public spectacle.

Crowds loved him. Newspapers couldn’t get enough. And businesses? They threw money at him to dangle their ads mid-climb.

Banks, movies, even life insurance companies (irony alert: none would insure him) paid Gardiner to promote their goods to the masses below.

Talk about a side hustle! In 1916, he drew 150,000 spectators to watch him scale Detroit’s 14-story Majestic Building. That’s like filling a modern NFL stadium to watch a guy play real-life Minecraft on a skyscraper.

When the Show Went South

But it wasn’t all confetti and cheers. In 1915, Gardiner faced a nightmare scenario while climbing the South Carolina State Capitol.

A misstep sent him plummeting 50 feet, shattering his ribs and damaging the building.

Did that stop him? Nope. He brushed off the dust, healed up, and kept climbing—though the incident spooked lawmakers.

Copycats soon emerged, many with far less skill. “They didn’t have nine lives,” one historian quipped.

Tragic accidents led cities to outlaw “buildering,” the now-official term for urban climbing (yes, it’s a real word—blend “bouldering” and “building”).

Gardiner himself vanished mysteriously in the 1920s. Rumors swirled that he fled to Paris, and some claimed a man matching his description was found dead at the Eiffel Tower’s base.

But the truth? It’s buried in history’s fog.

Buildering: From Gardiner to Spider-Man

Gardiner’s legacy didn’t just fade into the ether. He inspired a rogue’s gallery of modern daredevils.

Take Alain Robert, aka the “French Spider-Man,” who free-soloed Dubai’s 2,717-foot Burj Khalifa in 2011 (with a harness, but still).

Or Dan Goodwin, the 1980s “Spider-Dan,” who scaled Chicago’s Sears Tower using suction cups and a homemade Spider-Man suit.

Then there’s Angela Nikolau, a Russian rooftopper who merges Gardiner’s audacity with Instagram-era flair.

She’s scaled Malaysia’s 678.9-meter Merdeka 118—the world’s second-tallest building—in a ballet skirt, snapping selfies that’d give OSHA nightmares.

“Roof-topping is about capturing a moment from a view no one else sees,” she says, turning her death-defying climbs into NFT art.

Why Do They Do It?

Buildering isn’t parkour, though they’re cousins. Parkour focuses on efficiency; buildering is pure vertical theater.

And while cities crack down harder than ever, the thrill persists. Lucinda Grange, a British photographer, scales landmarks like the Chrysler Building in chic dresses, snapping photos mid-climb.

“It’s about the rush,” she admits, though she’s had her share of close calls with security.

Gardiner would’ve loved these modern rebels.

After all, he wasn’t just climbing for kicks—he was proving that human ambition could outpace fear. Even when the stakes were life-or-death. Especially then.

A Warning Label

Before you dust off your climbing shoes, a reality check: Buildering is wildly illegal and even more dangerous.

Modern builderers face fines, arrests, and worse. But for a rare few, the allure of the climb—the mix of adrenaline, art, and sheer defiance—is worth the risk.

As Gardiner showed over a century ago, sometimes the greatest view comes from the edge of the impossible.