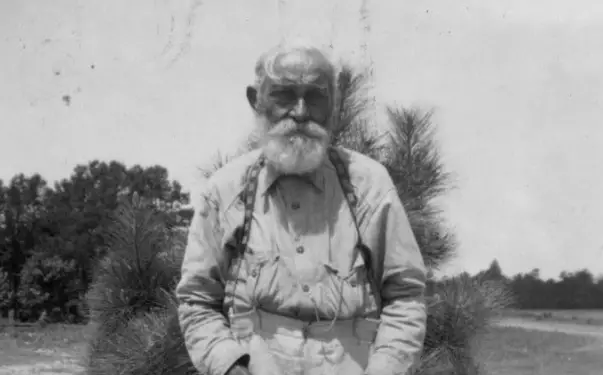

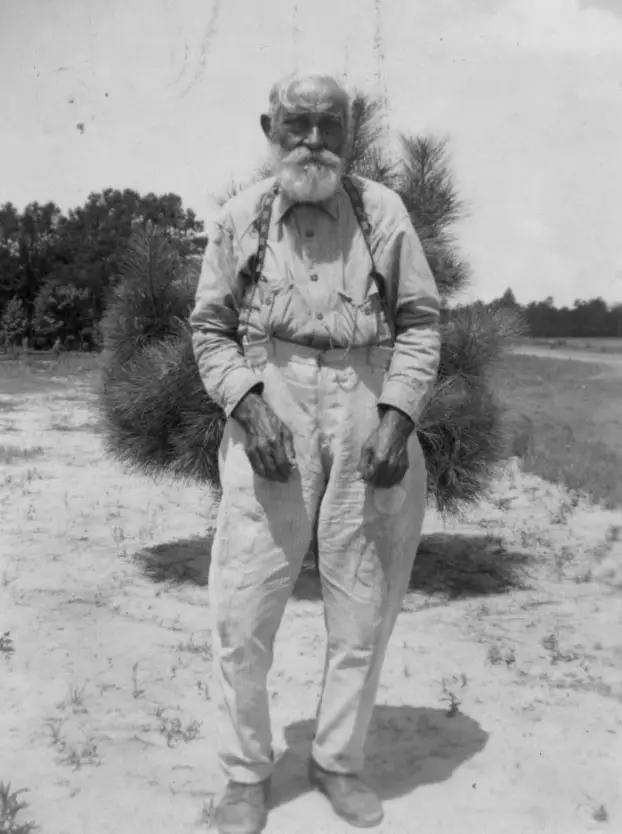

Preely Coleman’s Gripping Account of Slavery’s Horrors, a Near-Fatal Childhood Betrayal, and Texas Liberation in 1865

- Preely Coleman, born enslaved in 1852 near Newberry, South Carolina, endured an interstate sale as an infant amid the escalating demand for labor in Texas cotton fields.

- Narrowly escaped death in a violent prank by fellow children during the Civil War years, saved by a local plantation figure in rural Texas.

- Experienced the raw moment of emancipation in Alto, Texas, as Union victory rippled through the Confederacy, sparking immediate celebrations among the newly freed.

In the sweltering heat of a Texas afternoon, an elderly man named Preely Coleman sat down with federal interviewers, his voice steady yet laced with the dialect of a lifetime shaped by bondage.

“I’m Preely Coleman and I never gets tired of talking,” he began, recounting a saga that spanned the antebellum South, the brutal realities of plantation life, and the dawn of freedom.

At 85 years old in 1937, Coleman was one of thousands whose stories were captured by the Works Progress Administration’s Slave Narratives project, a New Deal initiative aimed at preserving firsthand accounts from the era of American chattel slavery.

His narrative, rich with details of African American resilience, offers a window into the human cost of an institution that defined the nation’s economy and divided its soul.

Coleman’s origins traced back to the fertile soils of Newberry County, South Carolina, where cotton plantations dominated the landscape in the mid-19th century.

Born around 1852 on the Souba family estate, roughly ten miles from the county seat, he entered a world where enslaved people outnumbered free residents in many districts.

The 1860 census revealed Newberry as a hub of agrarian wealth, with over 12,000 enslaved individuals toiling under a system that treated them as property to be bought, sold, and inherited.

Coleman’s mother, whose name echoes faintly through records, belonged to the Soubas, but family ties meant little in the face of profit. One of the Souba sons was his father, a fact that did not shield them from the auction block.

“My mammy tells me that a thousand times,” Coleman recalled, emphasizing how his parent ingrained the truth of their uprooting.

The sale came swiftly. At just a month old, Coleman and his mother were traded to Bob and Dan Lewis, two brothers eager to expand their holdings in the burgeoning Texas frontier.

This transaction reflected a broader pattern in the domestic slave trade, where over a million people were forcibly relocated from the Upper South to the Deep South and Southwest between 1790 and 1860, fueling the cotton boom that made the United States a global economic power.

The journey to Alto, Texas, in Cherokee County, took a full month, part of a massive influx that saw Texas’s enslaved population surge from about 5,000 in 1836 to more than 182,000 by the eve of the Civil War.

Alto itself emerged as a settlement in the 1830s, founded by figures like Colonel Robert F. Mitchell, who arrived with enslaved workers to clear land for what would become prosperous farms.

The Lewises’ plantation fit this mold, a sprawling operation where new arrivals like Coleman adapted to the harsh rhythms of frontier life.

Childhood on the Lewis place offered fleeting moments of joy amid the shadows of oppression. With plenty of other children around, games provided brief escapes.

Coleman described lively races under mulberry trees, where energy and speed could earn a quarter—a small fortune for an enslaved youth.

But innocence turned treacherous. Jealous of his consistent wins, the other children ambushed him one day, looping a rope around his neck and dragging him toward a deep spring at the hill’s base.

“I was nigh ’bout choked to death,” he said, his only defender a friend named Billy who fought desperately to free him.

The ordeal might have ended in tragedy had they not encountered Captain Henry Berryman, a white settler known in local lore for establishing the nearby Forest Hill Plantation in the late 1830s.

Berryman, who had migrated to the area with his own enslaved workforce to build a cattle ranch and log home, intervened decisively.

He cut the rope with his knife and revived Coleman by dunking him in the spring’s cool waters. Such acts of mercy, rare as they were, highlighted the unpredictable power dynamics on these isolated outposts.

As the nation hurtled toward conflict, the Civil War intruded on the plantation’s routines. Soldiers en route to key engagements paused for rest and provisions, turning the grounds into temporary camps.

Coleman vividly remembered troops heading to the Battle of Mansfield in Louisiana, a pivotal clash on April 8, 1864, during the Red River Campaign.

There, Confederate forces under Major General Richard Taylor, including Texas and Louisiana units totaling around 10,500 men, ambushed a larger Union army led by Nathaniel P. Banks, inflicting heavy casualties—over 2,200 Union losses, including 113 killed and 1,541 captured—in a stunning victory that halted the federal advance toward Shreveport.

These passing soldiers, likely Confederates bolstering Taylor’s ranks, brought news of the wider war, where battles like Mansfield underscored the South’s desperate defense of its way of life, including slavery.

| Milestone | Year | Location | Key Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth | 1852 | Near Newberry, South Carolina | Born on Souba family plantation to an enslaved mother; father was a Souba son |

| Sale and Relocation | 1852 | From South Carolina to Texas | Sold with mother to Bob and Dan Lewis for transport to Alto; journey lasted one month |

| Near-Death Incident | Mid-1850s | Alto, Texas | Ambushed by children in a prank; rescued by Captain Henry Berryman near Forest Hill Plantation |

| Resale to New Owners | Late 1850s | Alto, Texas | Bought by the Selman family for $1,500 (mother) plus Coleman as an addition |

| Field Labor Begins | Early 1860s | Selman Plantation, Texas | Transitioned from hoeing to plowing; strict schedule enforced by conch shell signals |

| Civil War Encounters | 1864 | En route to Mansfield, Louisiana | Hosted soldiers heading to the battle, participating in races for quarters |

| Emancipation | June 19, 1865 | Alto, Texas | Announced freedom in the fields; immediate celebrations followed |

| WPA Interview | 1937 | Tyler, Texas | Shared life story at age 85 as part of federal Slave Narratives project |

| Death | 1940 | Tyler, Texas | Passed away at approximately 88 years old; buried locally |

Life under the Selmans, who acquired Coleman and his mother after the Lewises lost their property, intensified as he grew. For $1,500 paid for his mother—with him “throwed in”—they joined a setup of five cabins arranged in a half-circle, typical of Texas plantations designed for surveillance and control.

By his teens, Coleman hoed fields before advancing to plowing, rising before dawn at the blow of a conch shell. Work ran from daylight to 11:30 a.m., resumed after a brief dinner until dusk, with no labor permitted on Sundays—a small concession in an otherwise relentless regime.

Footwear came in the form of stiff red russet shoes, mandated to protect against snags and stumps that littered the uncleared land. Meals varied by season: bread soaked in pot liquor or milk under summer trees, or in the winter kitchen, occasionally sweetened with honey.

Master Tom Selman, described as a good man despite his fondness for toddy kept ever-present on the dining table, oversaw this world where enslaved families navigated permissions for unions, like Coleman’s mother marrying John Selman en route to Texas with the owner’s consent.

Yet beneath this structure simmered the undercurrents of resistance and hope, amplified by wartime disruptions.

Texas, the last Confederate state to acknowledge the Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, delayed freedom’s arrival due to geographic isolation and deliberate suppression.

It was not until June 19, 1865—over two months after Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox—that Union General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston to enforce the order, birthing what would become Juneteenth, now a federal holiday commemorating the end of slavery in the United States.

For Coleman, the moment unfolded in the fields. “We was in the field and massa comes up and say, ‘You all is free as I is,'” he recounted, the words igniting shouts and songs that carried into the night.

In the chaotic aftermath, Coleman and his family moved to nearby plantations, hiring out labor in a sharecropping system that often mirrored bondage’s hardships.

Communities like Weeping Mary in Cherokee County emerged, founded by formerly enslaved sisters who purchased land to foster independence.

Coleman eventually settled in Tyler, Texas, where he lived until 1940, outlasting many peers from the era.

His story, preserved amid fading memories, raises haunting questions about the untold traumas passed down through generations—what other secrets did those mulberry tree races hide, and how many more voices like his remain buried in the soil of forgotten plantations?