Roosevelt’s Plea to Hitler: The Diplomatic Gambit Before Munich

In the tense summer of 1938, Europe stood on the edge of catastrophe.

Adolf Hitler, emboldened by his annexation of Austria, set his sights on the Sudetenland, a region of Czechoslovakia home to millions of ethnic Germans.

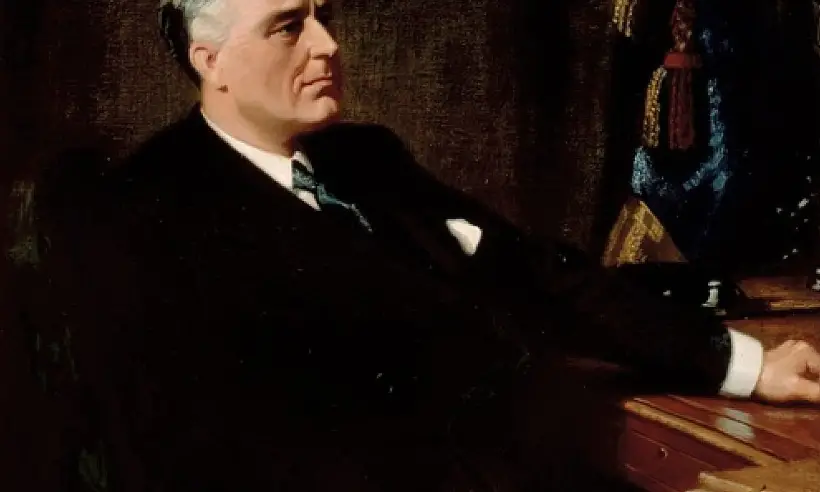

As tensions escalated, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt made a bold move.

From across the Atlantic, he sent a telegram to Hitler, urging him to avoid war and respect the sovereignty of 23 nations.

This little-known diplomatic effort, overshadowed by the Munich Agreement, sheds light on the desperate attempts to avert a second global conflict and the ultimate failure of appeasement policies.

The Rising Tensions in Europe

By 1938, Hitler’s aggressive foreign policy had alarmed the world.

His annexation of Austria in March, known as the Anschluss, marked a significant escalation.

The Sudetenland became his next target, with its 3 million ethnic Germans providing a pretext for intervention.

Czechoslovakia, fortified and allied with France, prepared to defend itself.

However, Britain and France, scarred by World War I, sought to avoid another conflict. They pursued appeasement, hoping concessions would satisfy Hitler.

The United States, officially neutral and isolationist, watched with growing concern.

Roosevelt, aware of the global implications of a European war, decided to intervene diplomatically.

His action was unusual, given America’s reluctance to engage in European affairs. Yet, he believed a direct appeal to Hitler might prevent catastrophe.

Roosevelt’s Message: A Plea for Peace

On September 26, 1938, Roosevelt sent a carefully worded telegram to Hitler.

He expressed alarm at the global fear of war, particularly over the Sudetenland crisis.

He urged Hitler to seek a peaceful resolution and requested assurances that Germany would not attack or invade 23 independent nations for at least 10 years, preferably 25 years.

The list was extensive, covering Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, The Netherlands, Belgium, Great Britain and Ireland, France, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Luxemburg, Poland, Hungary, Rumania, Yugoslavia, Russia, Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey, Iraq, the Arabias, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and Iran Roosevelt’s message.

Roosevelt’s appeal was not just about the immediate crisis.

He aimed to establish a framework for long-term peace.

He offered to mediate discussions on disarmament and international trade, suggesting economic cooperation could ease tensions.

His message reflected a hope that diplomacy could prevail, even as Hitler’s intentions grew clearer.

| Key Details of Roosevelt’s Message | Information |

|---|---|

| Date | September 26, 1938 |

| Recipient | Adolf Hitler, German Chancellor |

| Nations Listed | 23 independent nations, including Finland, Poland, and Iran |

| Non-Aggression Period Requested | Minimum 10 years, preferably 25 years |

| Additional Offers | Mediation, discussions on disarmament and trade |

Hitler’s Response: Defiance and Justification

Hitler responded on September 27, 1938, with a lengthy and defiant telegram.

He refused to accept responsibility for potential hostilities, blaming the Treaty of Versailles for Germany’s grievances.

He argued that the creation of Czechoslovakia had denied self-determination to the Sudeten Germans, leading to their oppression.

Hitler cited stark figures: 214,000 Sudeten German refugees had fled to Germany, countless had been killed or injured, and tens of thousands had been arrested Hitler’s reply.

He referenced his Nuremberg speech on September 13 and a memorandum on September 23, where he demanded the Sudetenland’s cession.

He noted that Czechoslovakia had agreed in principle, framing his actions as a response to Czech aggression.

Hitler’s tone was dismissive, showing no willingness to provide the assurances Roosevelt sought.

His response underscored his commitment to expansion, regardless of international appeals.

| Key Details of Hitler’s Response | Information |

|---|---|

| Date | September 27, 1938 |

| Main Argument | Blamed Treaty of Versailles and Czech oppression of Sudeten Germans |

| Statistics Cited | 214,000 refugees, countless dead, thousands injured, tens of thousands arrested |

| Proposals Referenced | Nuremberg speech (September 13), memorandum (September 23) |

The Munich Agreement: Appeasement in Action

While Roosevelt engaged Hitler, European leaders pursued a different strategy. On September 29-30, 1938, Britain, France, Germany, and Italy met in Munich.

The resulting Munich Agreement allowed Germany to annex the Sudetenland, home to over 3 million ethnic Germans.

Czechoslovakia, excluded from the talks, faced immense pressure from Britain and France to comply.

The agreement was signed by Neville Chamberlain, Édouard Daladier, Benito Mussolini, and Hitler, with Chamberlain famously declaring it brought “peace for our time” Munich Agreement.

The Munich Agreement had significant consequences.

Czechoslovakia lost its border fortifications, 70% of its iron and steel industry, and 3.5 million citizens.

Germany gained a substantial arsenal, aiding its later invasions of Poland and France.

The agreement, seen as a triumph at the time, is now regarded as a failed act of appeasement, emboldening Hitler’s aggression.

| Key Details of the Munich Agreement | Information |

|---|---|

| Date Signed | September 30, 1938 |

| Signatories | Hitler, Chamberlain, Daladier, Mussolini |

| Main Provision | German annexation of the Sudetenland |

| Impact on Czechoslovakia | Loss of fortifications, 70% of industry, 3.5 million citizens |

| Contemporary Reaction | Celebrated as preventing war; later seen as failed appeasement |

Analysis: A Clash of Approaches

Roosevelt’s message to Hitler stands in contrast to the appeasement policies of Britain and France.

While Chamberlain and Daladier sought to placate Hitler by conceding territory, Roosevelt attempted to set boundaries through diplomacy.

Historians view his effort as a bold but naive attempt to reason with a dictator bent on conquest.

“Roosevelt’s appeal was a significant moment, showing America’s growing concern for global stability,” says historian David Faber.

“But it underestimated Hitler’s resolve to pursue his expansionist goals” Sudetenland crisis.

The Munich Agreement, signed days later, highlighted the failure of appeasement.

By allowing Hitler to annex the Sudetenland, Britain and France weakened Czechoslovakia and emboldened Germany.

Roosevelt’s action also reflected the U.S.’s limited influence in 1938.

America’s isolationist policies restricted Roosevelt’s ability to act decisively.

Yet, his message foreshadowed the U.S.’s eventual entry into World War II, showing early awareness of the global stakes.